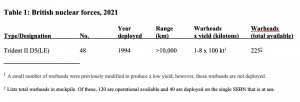

Of all the nuclear weapon states, the United Kingdom has moved the furthest toward establishing a minimum nuclear deterrent. The United Kingdom has a stockpile of approximately 225 nuclear warheads, of which up to 120 are operationally available for deployment on four Vanguard-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). This estimate is based on publicly available information regarding the size of the British nuclear arsenal, conversations with UK officials, and analysis of the nuclear forces structure. The SSBNs, each of which has 16 missile tubes, constitute the United Kingdom’s sole nuclear platform, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) comprise its sole nuclear delivery system. The United Kingdom is the only nuclear weapon state that operates a posture with a single deterrence system (Table 1).

The United Kingdom’s nuclear posture

Carrying approximately 40 warheads, one of the four SSBNs is deployed at sea at all times in what is called a Continuous At-Sea Deterrent (CASD) posture. Two of the submarines remain in port and can be deployed on short notice, while the fourth remains in overhaul and could not be quickly deployed, if at all. The patrol SSBN operates at “reduced alert;” that is, its capability to fire its missiles is measured in days, rather than a few minutes (as during the Cold War). Its missiles are also kept in a “detargeted” mode—target coordinates are stored in the submarine’s launch control center instead of in the navigational system of each missile.

To safeguard against the degradation of its nuclear command, control, and communications in wartime, the United Kingdom uses a system of handwritten letters to command its submarines in the event an adversarial strike incapacitates the country’s leadership. On their first day in office, the Prime Minister is expected to offer preplanned instructions regarding the United Kingdom’s nuclear response, which are said to include options like “Put yourself under the command of the US, if it is still there,” “Go to Australia,” “Retaliate,” or “Use your own judgment” (Norton-Taylor 2016).

British SSBNs, which carry out secondary tasks such as scientific data collection while on patrol, are based in southwestern Scotland at the Naval Base Clyde at Faslane, which has access to the Irish Sea. Nonoperational warheads are stored at the Royal Naval Armaments Depot (RNAD) at Coulport, approximately three kilometers west of the base.

The United Kingdom’s nuclear weapons stockpile

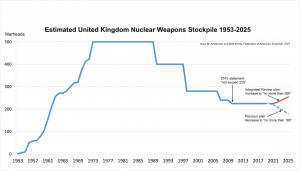

Unlike the United States, the United Kingdom has not declassified the history of its nuclear weapons stockpile size. Over the past two decades, however, the United Kingdom has made several declarations about reducing the sizes of its nuclear inventory and operationally available warheads. In 2006, the UK government announced that they would be “reducing the number of operationally available warheads from fewer than 200 to fewer than 160” (Ministry of Defence 2006, 17). It is believed that around that time, the UK nuclear stockpile included 240 to 245 nuclear warheads. In May 2010, Foreign Secretary William Hague declared, “[f]or the first time, the government will make public the maximum number of warheads that the United Kingdom will hold in its stockpile—in [the] future, our overall stockpile will not exceed 225 nuclear warheads” (Hague 2010, col. 181). The Ministry of Defence subsequently revealed that these reductions to a 225-warhead ceiling had already been completed by May 2010 (UK Ministry of Defence 2013).

Later that year, in October 2010, the Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) declared that the United Kingdom would “reduce the number of warheads onboard each submarine from 48 to 40; reduce our requirement for operationally available warheads from fewer than 160 to no more than 120; reduce our overall nuclear weapon stockpile to no more than 180; [and] reduce the number of operational missiles on each submarine” (HM Government 2010, 38). In June 2011, the Secretary of Defence announced to parliament that some of these proposed changes had already been implemented: “at least one of the VANGUARD class ballistic missile submarines (SSBN) now carries a maximum of 40 nuclear warheads” (Fox 2011).

In its 2015 Strategic Defence and Security Review, the UK Government reaffirmed its plans to cut the size of the nuclear arsenal. By this point, the number of operationally available nuclear warheads had already been reduced from fewer than 160 to no more than 120, and all Vanguard- class SSBNs “now carry 40 nuclear warheads and no more than eight operational missiles” (Fallon 2015). The 2015 strategic review restated that the overall size of the nuclear stockpile, including non-deployed warheads, was expected to decrease to no more than 180 by the mid-2020s (HM Government 2015, 34). Despite these stated intentions, it is believed that throughout the decade the overall size of the UK nuclear stockpile remained constant, at approximately 225 nuclear weapons in total. Warheads removed from service during this time were put into storage, but not dismantled.

In its 2021 Integrated Review, the UK Government suddenly reversed decades of gradual disarmament policies and announced a significant increase in the upper limit of the United Kingdom’s nuclear inventory, up to no more than 260 warheads (HM Government 2021, 76). This decision joins the United Kingdom together with China and Russia as the three members of the so- called P5 NPT countries to increase the sizes of their nuclear stockpiles. In clarifying statements, UK officials noted that the target of 180 warheads promised in the 2010 and 2015 SDSRs “was indeed a goal, but it was never reached, and it has never been our cap,” stating that 225 remained the cap even after the 2015 SDSR explicitly declared that “we will reduce the overall nuclear weapon stockpile to no more than 180 warheads” (Liddle 2021; HM Government 2015, 34). In a speech to the Conference on Disarmament, foreign minister James Cleverly stated that the 260 warheads “is a ceiling, not a target, and is not our current stockpile” (Cleverly 2021).

Because the United Kingdom has not declassified the history of its nuclear weapons stockpile size, illustrating how the stockpile has fluctuated over the years comes with considerable uncertainty. Based on documents previously published by the British government, statements made by government officials, and analysis of the British nuclear weapons force structure over the years. Figure 1 displays our estimates for the overall size of the United Kingdom’s nuclear arsenal between 1953 and 2025.

The degree to which the Johnson’s government’s policy change will affect the United Kingdom’s targeting requirements remains to be seen; however, the Integrated Review states that the stockpile increase comes in response to “the evolving security environment, including the developing range of technological and doctrinal threats” (HM Government 2021, 76). After publication of the review, Defence Secretary Ben Wallace explained this included Russian ballistic missile defenses: “We have to . . . maintain a credible deterrent to reflect and review what the Russians and others have been up to in the last few years. We have seen Russia invest strongly in ballistic missile defense. They have planned and deployed new capabilities. That means if [the UK deterrent is] going to remain credible, it has to do the job . . . . A quite clear study of how effectively warheads work and how they reenter the atmosphere means you have to make sure they’re not vulnerable to ballistic missile defense. Otherwise they no longer become credible” (Wallace 2021).

It is notable that while Russia is singled out as “the most acute direct threat to the UK,” the Integrated Review also includes what appears to be a subtle—but clear—nuclear threat against Iran, despite the fact that Iran does not have nuclear weapons: After assuring that “the UK will not use, or threaten to use, nuclear weapons against any non-nuclear weapon state party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons 1968 (NPT),” the document states that “[t]his assurance does not apply to any state in material breach of those non-proliferation obligations” (HM Government 2021, 77).

In addition to the warhead cap increase, the Integrated Review also reversed longstanding transparency practices and stated that the United Kingdom will “no longer give public figures for our operational stockpile, deployed warhead or deployed missile numbers” (HM Government 2021, 77). This is a mirror image of the Trump administration’s abrupt decision to keep the nuclear stockpile number secret after nearly a decade of relative transparency under the Obama administration (Kristensen 2020).

To increase its overall stockpile, the UK will likely bring warheads previously retired for dismantlement back into the stockpile. Under the UK Atomic Weapons Establishment’s (AWE) Stockpile Reduction Program, warhead disassembly is undertaken at AWE Burghfield. According to the Ministry of Defence,

The main components from warheads disassembled as part of the stockpile reduction programme have been processed in various ways according to their composition and in such a way that prevents the warhead from being reassembled. A number of warheads identified in the programme for reduction have been modified to render them unusable whilst others identified as no longer being required for service are currently stored and have not yet been disabled or modified (UK Ministry of Defense 2013).

These reserve warheads are either stored at the Royal Naval Armaments Depot Coulport or at AWE Burghfield. It is unclear how many stored warheads could be quickly reconstituted in light of the UK Government’s recent decision to raise its warhead ceiling; however, it is possible that a few dozen warheads could be returned to the stockpile over the coming years.

Nuclear modernization and the UK sea-based deterrent

Despite decades of nuclear weapons reductions, the United Kingdom—with broad parliamentary support—has committed to replacing its current fleet of Vanguard-class SSBNs with brand-new boats. The new Dreadnought-class SSBNs are expected to enter service in the early 2030s and have a service life of at least 30 years (Mills 2020). The four boats will be named Dreadnought, Valiant, Warspite, and King George VI (UK Ministry of Defence 2019).

The Dreadnought-class SSBNs will have new “Quad Pack” Common Missile Compartments that are being designed in cooperation with the US Navy to also equip the United States’ new Columbia-class SSBNs. Each “Quad Pack” Common Missile Compartment holds four launch tubes, and each Dreadnought-class SSBN will have three Quad Packs onboard for a planned total of 12 launch tubes—a reduction from the 16 launch tubes currently carried by the UK’s Vanguard-class submarines. Technical problems and quality control issues have resulted in the delayed delivery of the missile launch tubes for the Common Missile Compartment; however, in April 2020 the first four tubes were delivered and have since been welded into the first UK Quad Pack (UK Ministry of Defence 2020a). In July 2020, two more missile tubes were received by the submarine building facility at Barrow-in-Furness, meaning that half of the tubes required for the lead Dreadnought boat have now been delivered and are in the process of being integrated into the pressure hull (UK Ministry of Defence 2020a).

The United Kingdom’s nuclear deterrent relies heavily on American nuclear infrastructure, to the point where its own independence has long been in question. The United Kingdom does not own its own missiles, but has title to 58 Trident SLBMs from a pool of missiles shared with the United States Navy. The UK Government is also participating in the US Navy’s current program to extend the service life of the Trident II D5 (the life-extended version will be known as D5LE) missile to the early 2060s (Mills 2021).

Additionally, the current UK warhead, which is called Holbrook, is believed to be highly similar to the United States’ W76-0 warhead—so similar that it has appeared in the US Department of Energy’s “W76 Needs” maintenance schedule (Kristensen 2006). As part of its Nuclear Warhead Capability Sustainment Programme, the United Kingdom is currently refurbishing its warheads for incorporation onto the US-supplied Mk4A aeroshell, which is an upgraded version of the Mk4 that includes an improved MC4700 Arming, Fuzing, and Firing (AF&F) system. UK officials have suggested that “the Mk4A programme will not increase the destructive power of the warhead;” however, the new AF&F system reportedly includes new technology that significantly increases the system’s ability to conduct hard-target kill missions (Norton-Taylor 2011; UK Ministry of Defence 2016; Kristensen, McKinzie, and Postol 2017).

These warhead upgrades are taking place at the Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) facility at Aldermaston, from where the warheads are transported on trucks north to the Royal Naval Armaments Depot (RNAD) Coulport, near Glasgow. Warhead scheduled for dismantlement are shipped to AWE Burghfield eight kilometers (4.8 miles) northeast of Aldermaston. The UK disarmament group Nukewatch has tracked these transports and assesses that by the end of 2020, two SSBNs had been loaded with Mk4A-upgraded warheads (Nukewatch 2020).

In February 2020, the UK defence secretary announced the start of a new warhead program to eventually replace the current warhead (UK Ministry of Defence 2020b). The announcement was preempted by the commander of US Strategic Command, who leaked during Senate testimony that the United States’ W93/Mk7 program “will also support a parallel Replacement Warhead Program in the United Kingdom” (Richard 2020). In April 2020, the UK defence secretary sent a letter to US members of Congress, lobbying them in support of the new warhead and describing it as “critical . . . to the long-term viability of the UK’s nuclear deterrent” (Borger 2020). The UK Ministry of Defence subsequently suggested that just like the similarities between the current US and UK warheads, the UK’s replacement warhead will be very similar to the US W93: “It’s not exactly the same warhead but . . . there is a very close connection in design terms and production terms” (Lovegrove 2020).

Concerns and issues for the future

The increasing costs and poor management of the United Kingdom’s nuclear complex have long been sources of frustration. The 2015 SDSR suggested that the costs of building the four new submarines would be £31 billion, an increase of £6 billion from 2011 estimates (HM Government 2015, 36, 2011, 10). The UK Government also set aside a contingency fund of £10 billion to cover possible cost overruns. In December 2020, the UK Ministry of Defence reported to Parliament that approximately £8.5 billion had been spent on the program as of March 2020, of which £1.6 billion had been spent over the previous 12 months (UK Ministry of Defence 2020a). Altogether, the National Audit Office (NAO) reported in 2018 that the Ministry of Defence was facing an “affordability gap” of £2.9 billion in its military nuclear spending between 2018 and 2028 (National Audit Office 2018, 36).

In addition to these longstanding cost concerns, in 2020 both the NAO and the parliamentary Public Accounts Committee published reports indicating that three crucial nuclear infrastructure projects would be delayed between 1.7 and 6.3 years, with costs increasing by over £1.3 billion due to poor management (National Audit Office 2020, 21; Committee of Public Accounts 2020, 3). One of these infrastructure projects is MENSA, a new warhead assembly and disassembly facility at Aldermaston that has been delayed by six years and overspent by 146 percent (National Audit Office 2020, 4). Other critical nuclear projects—such as Pegasus, for handling enriched uranium components, and Hydrus, for conducting hydrodynamic-radiographic experiments—have been plagued by similar issues (Plant 2020).

In a bid to resolve some of these issues related to management and oversight, in November 2020 the Ministry of Defence announced a renationalization of the Atomic Weapons Establishment, which had previously been government-owned but contractor-operated via a consortium led by Lockheed Martin (Wallace 2020).

Another future concern for the United Kingdom’s nuclear deterrent lies with the prospect of Scottish independence. Naval Base Clyde, where the United Kingdom’s SSBNs are ported, is in Scotland, at Faslane on the Gare Loch. A 2013 Scottish government white paper clearly stated that if Scotland voted for independence the following year, “we would make early agreement on the speediest safe removal of nuclear weapons a priority. This would be with a view to the removal of Trident within the first term of the Scottish Parliament following independence” (Scottish Government 2013, 14). Although Scotland narrowly voted to remain part of the United Kingdom, it is increasingly likely that the United Kingdom’s decision to exit the European Union—a decision opposed by the majority of Scotland—could soon trigger another referendum. Although several potential relocation candidates have been identified by external analysts—such as HM Naval Base Devonport in Plymouth—the costs and logistics involved with relocating the United Kingdom’s SSBN force would be prohibitive and could prompt the UK Government to reconsider its current plans to modernize its nuclear deterrent (Chalmers and Chalmers 2014; Norton-Taylor 2013).

By Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda

Sources:

Borger, J. 2020. “UK lobbies US to support controversial new nuclear warheads.” The Guardian. 1 August. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/01/uk-trident-missile-warhead-w93-us-lobby.

Chalmers, H., and Chalmers, M. 2014. “Relocation, Relocation, Relocation: Could the UK’s Nuclear Force be Moved after Scottish Independence?” Royal United Services Institute. August. https://rusi.org/sites/default/files/201408_op_relocation_relocation_relocation.pdf.

Cleverly, J., Minister of State. 2021. “Conference on Disarmament: Minister Cleverly’s Address on the Integrated Review.” March 26. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/conference-on-disarmament-minister-cleverlys-address-on-the-uk-integrated-review

Committee of Public Accounts. 2020. “Defence Nuclear Infrastructure: Second Report of Session 2019–21.” House of Commons. HC 86. 13 May. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmselect/cmpubacc/86/86.pdf.

Fallon, M. 2015. “Statement on Nuclear Deterrent.” Daily Hansard, Col. 4WS. 20 January. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201415/cmhansrd/cm150120/wmstext/150120m0001.htm.

Fox, L. 2011. “Statement on Nuclear Deterrent.” Daily Hansard, Col. 50-51WS. 29 June. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmhansrd/cm110629/wmstext/110629m0001.htm.

Hague, W. 2010. “Statement on foreign affairs and defense.” Daily Hansard, Col. 181. 26 May. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmhansrd/cm100526/debtext/100526-0005.htm.

HM Government. 2010. “Securing Britain in an Age of Uncertainty: The Strategic Defence and Security Review.” Cm 7948. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/62482/strategic-defence-security-review.pdf.

HM Government. 2011. “The United Kingdom’s Future Nuclear Deterrent: Initial Gate Parliamentary Report.” May. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/27399/submarine_initial_gate.pdf.

HM Government. 2015. “National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015: A Secure and Prosperous United Kingdom.” Cm 9161. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/555607/2015_Strategic_Defence_and_Security_Review.pdf.

HM Government. 2021. “Global Britain in a competitive age The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy:” CP 403. March. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/969402/The_Integrated_Review_of_Security__Defence__Development_and_Foreign_Policy.pdf.

Kristensen, H. M. 2006. “Britain’s Next Nuclear Era.” FAS Strategic Security Blog. 7 December. https://fas.org/blogs/security/2006/12/britains_next_nuclear_era/.

Kristensen, H. M. 2020. “Trump Administration Again Refuses To Disclose Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Size.” FAS Strategic Security Blog. 3 December. https://fas.org/blogs/security/2020/12/nuclear-stockpile-denial-2020/.

Kristensen, H. M., M. McKinzie, and T. Postol. 2017. “Warhead ‘Super-Fuze’ Increases Targeting Capability of US SSBN Force.” FAS Strategic Security Blog, March 2. https://fas.org/blogs/security/2017/03/super-fuze/.

Liddle, A. (@AidanLiddle). 2021. “That cap was maintained in 2015. 180 was indeed a goal, but it was never reached, and it has never been our cap. And by the way, we’re talking about ceilings, not targets, or indeed our actual numbers.” Tweet. March 16. https://twitter.com/AidanLiddle/status/1371912132141445120.

Lovegrove, S. 2020. “Oral evidence: MoD Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20, HC 1051.” House of Commons Defence Committee. Q31. 8 December. https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/1350/pdf/.

Mills, C. 2020. “Nuclear weapons at a glance: United Kingdom.” House of Commons Library Briefing Paper No. 9077. 9 December. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9077/.

Mills, C. 2021. “The cost of the UK’s strategic nuclear deterrent.” House of Commons Library Briefing Paper No. 8166. 2 March. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8166/.

National Audit Office. 2018. “The Defence Nuclear Enterprise: a landscape review.” HC 1003, Session 2017–2019. 22 May. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/The-Defence-Nuclear-Enterprise-a-landscape-review.pdf.

National Audit Office. 2020. “Managing infrastructure projects on nuclear-regulated sites.” HC 19, Session 2019-20. 10 January. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Managing-infrastructure-projects-on-nuclear-regulated-sites.pdf.

Norton-Taylor, R. 2011. “Trident more effective with US arming device, tests suggest.” April 6. http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2011/apr/06/trident-us-arming-system-test

Norton-Taylor, R. 2013. “The uncomfortable costs of moving Trident.” The Guardian. 10 July. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/jul/10/costs-moving-trident-analysis.

Norton-Taylor, R. 2016. “Theresa May’s first job: decide on UK’s nuclear response.” The Guardian. 12 July. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jul/12/theresa-mays-first-job-decide-on-uks-nuclear-response.

Nukewatch. 2020. “Warhead convoy movements summary 2020.” https://www.nukewatch.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Convoy-log-2020.pdf.

Plant, T. 2020. “Britain’s Nuclear Projects: Less Bang and More Whimper.” Royal United Services Institute. 22 January. https://www.rusi.org/commentary/britain%E2%80%99s-nuclear-projects-less-bang-and-more-whimper.

Richard, C. 2020. “Statement of Admiral Charles A. Richard, Commander, United States Strategic Command, Before the Senate Committee on Armed Services.” 13 February. https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Richard_02-13-20.pdf.

Scottish Government. 2013. “Scotland’s Future: Your Guide to an Independent Scotland.” 26 November. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-future/.

UK Ministry of Defence. 2006. “The Future of the United Kingdom’s Nuclear Deterrent.” White Paper, December. www.fas.org/nuke/guide/uk/doctrine/sdr06/WhitePaper.pdf.

UK Ministry of Defence. 2013. Response to Freedom of Information Act request made by Rob Edwards. Ref. 25-03-2013-173601-014. July 25. https://robedwards.typepad.com/files/mod-foi-response-on-dismantling-nuclear-weapons.pdf.

UK Ministry of Defence. 2016. “Defence in the media: 8 June 2016.” Blog Post. 8 June. https://modmedia.blog.gov.uk/2016/06/08/defence-in-the-media-8-june-2016/.

UK Ministry of Defence. 2019. “Defence Secretary praises 50 years of nuclear service as new submarine is named.” Press release. 3 May. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/defence-secretary-praises-50-years-of-nuclear-service-as-new-submarine-is-named.

UK Ministry of Defence. 2020a. “The United Kingdom’s future nuclear deterrent: the 2020 update to Parliament.” 17 December. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-united-kingdoms-future-nuclear-deterrent-the-2020-update-to-parliament/the-united-kingdoms-future-nuclear-deterrent-the-2020-update-to-parliament.

UK Ministry of Defence. 2020b. “Defence Secretary announces programme to replace the UK’s nuclear warhead.” 25 February. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/defence-secretary-announces-programme-to-replace-the-uks-nuclear-warhead.

Wallace, B. 2020. “Defence Update.” Daily Hansard, HCWS544. 2 November. https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2020-11-02/debates/20110250000009/DefenceUpdate.

Wallace, B. 2021. Interview on BBC’s Andrew Marr Show, 21 March. https://twitter.com/BBCPolitics/status/1373578535944740869

Featured image: Nuclear submarine HMS Vanguard arrives back at HM Naval Base Clyde, Faslane, Scotland following a patrol. Photo: CPOA(Phot) Tam McDonald/MOD accessed via Wikimedia Commons. Open Government License version 1.0.

Tehran Institute For International Studies tiis

Tehran Institute For International Studies tiis