The Great Game was a rivalry between the 19th-century British and Russian empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Afghanistan, Persia and Tibet. The two colonial empires used military interventions and diplomatic negotiations to acquire and redefine territories in Central and South Asia. Russia conquered Turkestan, and Britain expanded and set the borders of British India. By the early 20th century, a line of independent states, tribes, and monarchies from the shore of the Caspian Sea to the Eastern Himalayas were made into protectorates and territories of the two empires. — Wikipedia

Today, a new Great Game is in its early innings, to use a baseball analogy. The players are Russia, China and the United States, and the playing field is the Arctic.

As an Arctic nation, Canada has a role to play, but it’s a role that is being diminished by the United States, which sees Canada as less a partner than a nation vulnerable to attack that needs protecting.

Is this the reason President Donald Trump has been musing about making Canada the 51st state? Steve Bannon thinks so. The former top Trump aide in an interview with Global News said that Canadians are “misreading the situation” by focusing on tariffs, and that Trump’s real interest in Canada is strategic and geopolitical:

“The world is now coming to Canada, and it’s coming in a big way,” Bannon says with a prophet’s conviction.

“You were isolated before. You’re not isolated now.”

That’s because, Bannon says, the Arctic is going to be the “Great Game of the 21st century” and a military weakness that he calls Canada’s “soft underbelly.”

.

.

Warming

Once considered too remote, too cold, and too inhospitable for civilization, the Arctic has been transformed by global warming.

Over the past 35 years, the Arctic has warmed more than any other region on earth – by 3.1 degrees in the coldest six months of the year, October to May.

When sea ice is lost, the sunlight is no longer reflected back to the atmosphere, but rather gets absorbed into the open ocean. This exacerbates ocean warming and forms a warming cycle. Warmer water temperatures delay the growth of ice in fall and winter, and the ice melts faster in the spring, exposing patches of open ocean for longer periods during summer, and further warming the ocean.

According to NASA, Arctic sea ice measured in September – when it is thinnest — is now declining at a rate of 13.2% per decade.

Along with calving glaciers, shrinking ice caps and disappearing sea ice, evidence of Arctic warming can also be seen in the thawing of permafrost.

It had been assumed that the melting of the top layer of tundra that remains frozen year-round would be a slow process, releasing carbon as the ground thawed. In fact, the permafrost melt is happening much quicker than expected. Scientists studying the phenomenon are finding “Instead of a few centimetres of thaw a year, several metres of soil can destabilize within days. Landscapes collapse into sinkholes. Hillsides slide away to expose deep permafrost that would otherwise have remained insulated,” states CBC.

In some places the thaw is happening so fast, the earth is swallowing up equipment left there to study it, Global News reports. The fast-melting areas are known to contain the most carbon, meaning that permafrost is probably going to release 50% more greenhouse gases than expected, including methane which is far more efficient than CO2 at trapping heat in the atmosphere.

One-fifth of Arctic permafrost is now vulnerable to global warming, according to a University of Guelph biologist, whose research was published in ‘Nature’.

Environmentalists, First Nations and other residents in the sparsely populated Arctic decry the effects of global warming, but where some see loss of animal habitat, like polar bears, in the melting ice, and a disappearing way of life for Inuit hunters, others see opportunity.

.

.

Territory Grab

A “territory grab” is happening in the Arctic, as polar nations jostle to control their share of a vast expanse of ocean and land that is rich in natural resources, and as the ice retreats, is beginning to open new trans-polar shipping routes that hold great promise for seaborne trade.

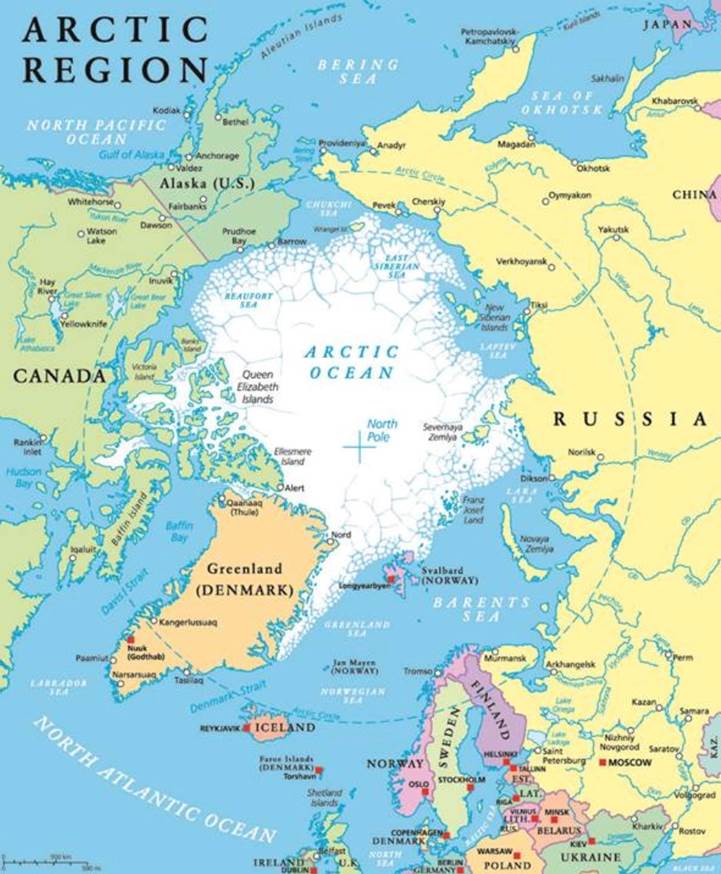

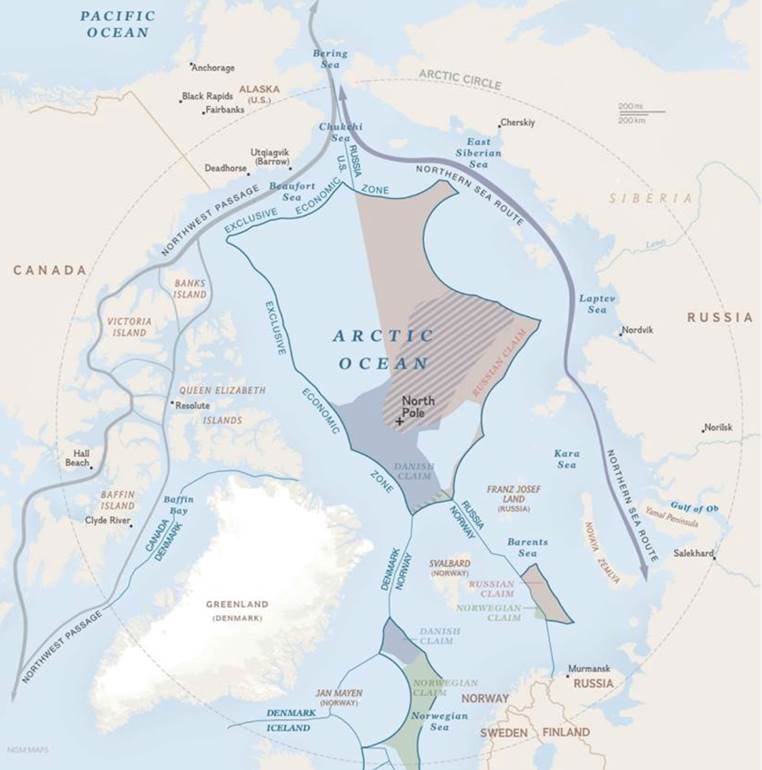

Who has jurisdiction over the North Pole, the Arctic Ocean, inland seas and land masses that we refer to as the Arctic? Control over all of this 20-million-square kilometer territory including “exclusive economic zones” (EEZs), is divided among the eight Arctic states: Canada, the United States, Russia, Norway, Denmark/Greenland, Iceland, Sweden and Finland.

EEZs are zones prescribed by the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Within these zones, a state has the right to explore and extract marine resources including hydrocarbons underneath the seabed, and energy produced from water and wind. EEZs stretch out 200 nautical miles from the coast. An Arctic nation, within the EEZ, has rights below the the ocean surface, but nobody owns the surface – they are known as international waters. The North Pole and the surrounding Arctic Ocean, for example, are not owned by any one country.

This sort-of shared ownership has caused some disputes over what is considered to be an international seaway and who has the right of passage. Six of the eight Arctic nations regard parts of the Arctic seas as their own. A country that ratifies the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea has 10 years to make claims on a continental shelf that gives it rights to resources on or below the shelf’s seabed; Norway, Russia, Canada and Denmark all have claims on continental shelves below their EEZs. The US has signed the convention but hasn’t ratified it.

When the Arctic Ocean was covered with a thick sheet of ice, this arrangement worked reasonably well, with little conflict. But the disappearance of the ice has stirred the imaginations of polar nations intent on taking advantage of more accessible natural resources and shipping routes.

If current climate trends continue, scientists estimate that the Arctic Ocean will be ice-free by mid-century. To clarify, that means sometime between 2030 and 2050, in September, the month with the least amount of ice cover, the Arctic Ocean will be entirely uncovered by ice.

Russia was the first to claim Arctic ownership beyond its territory, in 2007. Russia has also reportedly been expanding infrastructure along its northern coast to exploit natural gas reserves.

Canada claims ownership of the Arctic Ocean archipelago. To asserts its claims, the country has created a new research center, is developing autonomous submarines, and conducting search and rescue exercises in anticipation of growing ship traffic in the Northwest Passage.

But countries’ investment in the Arctic is rather un-even. Despite having the second largest amount of land mass within the Arctic Circle, behind Russia, Canada has spent very little, as has the United States with only the northern third of Alaska considered to be Arctic.

The big spenders are Russia and Norway. National Geographic notes that Russia has “greatly expanded its military forces in the Arctic, becoming, by most measures, the dominant cold-weather player.” Russia’s northern fleet is the largest in the world at 60 ice breakers and another 10 under construction. Norway has expanded its ice-capable fleet to 11 ships. Both countries have invested heavily in oil and gas development.

To be fair, Canada and the US operate bases in the Northwest Territories and Alaska capable of dispatching troops, aircraft and submarines. NATO countries regularly train for cold-weather conflict.

However, compared to Russia, and for that matter, China, not even a polar nation, Canada’s Arctic efforts pale. The government has no official Arctic policy and there is an extensive list of unfulfilled infrastructure promises including no high-speed Internet. The only significant project has been a paved road completed to the Arctic coast at Tuktoyaktuk in the Northwest Territories.

Lately China has become more interested in the Arctic, eyeing less ice cover as an opportunity to expand its ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI). The ‘Polar Silk Road’ would be an extension of its ambitious plans for a series of BRI infrastructure spends designed to create a trading orbit in southern Asia. The Polar Silk Road includes a potential shipping route across the Pacific and the development of energy and mining resources in the region, plus fishing and tourism.

The country is hoping to diversify its energy resources away from the Persian Gulf and Africa, by investing in Russia’s Yamal LNG complex and in Norway’s oil and gas fields.

In 2013 China was granted observer status on the Arctic Council, an inter-governmental discussion forum.

The combined Arctic moves of Russia and China have raised alarm bells in Washington, which fears its old Cold War enemies are planning to exercise territorial ambitions in the far north.

During Trump’s first term, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned his fellow foreign ministers at a meeting of the Arctic Council –– that the Arctic is emerging as a new “Great Game” between the US, Russia and China (notice Canada is not included), or maybe even a renewed Cold War.

Pompeo called out Russia’s claim over international waters of the Northern Sea Route and its moves to re-open military bases along the route as commercial shipping activity increases. And he disparaged China for even claiming to have a say in Arctic policy, noting that “the shortest distance between China and the Arctic is 900 miles.”

“Beijing claims to be a near-Arctic state,” Pompeo said, referring to China’s 2018 white paper on the Arctic. “There are Arctic states and non-Arctic states. No third category exists. China claiming otherwise entitles them to exactly nothing.”

For critics who thought that Pompeo shouldn’t be using the Arctic Council to make pronouncements of a political or military nature, he had this to say:

“We’re entering a new age of strategic engagement in the Arctic, complete with new threats to Arctic interests and its real estate.”

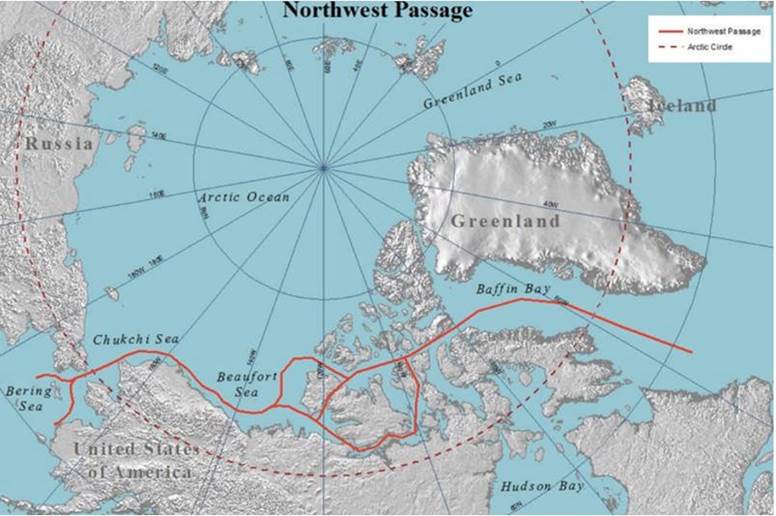

And in keeping with the Trump administration’s pugilistic approach to Canada, Pompeo disputed Canada’s claim to the Northwest Passage as internal waters, arguing the waters should be considered international.

As Russia, China, and increasingly, the US flex their Arctic muscles, Canada is the 90-pound weakling in the gym – having instituted a five-year ban on offshore energy exploration.

Ice-free Shipping

The opening of polar sea routes as a consequence of melting ice is a double-edged sword. On the one hand it presents a huge opportunity for polar nations to increase trade and to drastically cut transportation expenses. Yet increased commercial activity also heightens the possibility of conflict especially in an area where ownership to surface and undersea rights isn’t always clear.

Pompeo told his Arctic Council peers that new, ice-free sea lanes could become “21s century Suez and Panama Canals,” which would “potentially slash the time it takes to travel between Asia and the West by as much as 20 days.”

Indeed, a ship sailing from East Asia to Western Europe through the Northwest Passage, instead of having to go through the Panama Canal, could potentially cut 10,000 kilometers from the voyage. Imagine how much fuel that would save shipping companies, and crewing costs, plus the opportunity to deploy more vessels more frequently.

Melting sea ice is already opening up the Arctic Ocean. Climate scientists at UCLA in California, studying the impact of rising temperatures on shipping, found that by mid-century, ships will be able to travel the Northern Sea Route for three months during the summer without icebreakers.

In 2018 a Danish freighter owned by Maersk became the first container ship to sail through the Northern Sea Route.

.

.

Resource Treasure Chest

At Ahead of the Herd we always follow the money to discover the reasons behind most decisions. It’s no exception with the Arctic, which contains a veritable treasure trove of natural resources – mostly oil and gas but some minerals too.

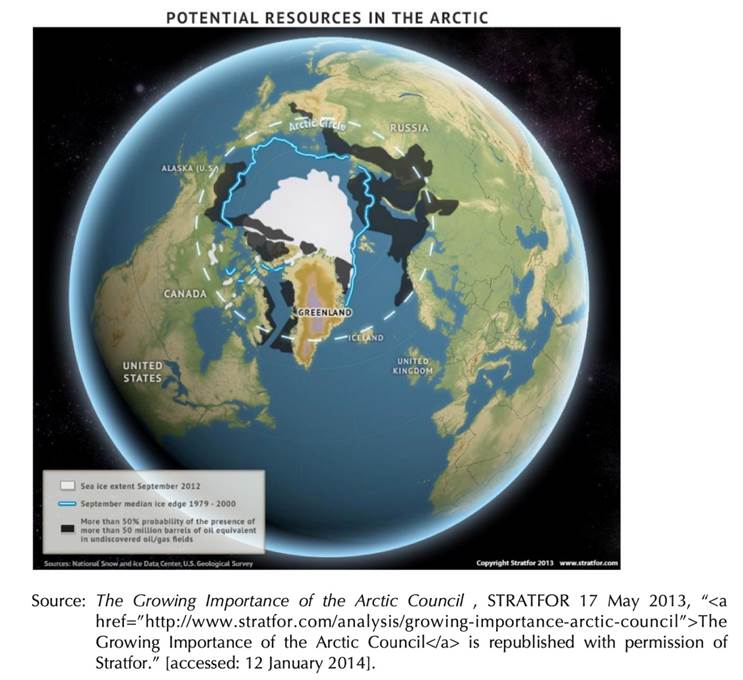

According to the US Geological Survey, the Arctic Circle (areas beyond the 200-nautical-mile economic exclusion zones are international ) contains up to 30% of the world’s undiscovered gas and 13% of its oil.

The Beaufort Sea off the coast of the Northwest Territories holds an estimated 56 trillion feet of natural gas and 8 billion barrels of oil.

Among the non-energy minerals hidden within the Arctic’s barren lands are coal, diamonds, uranium, phosphate, nickel and platinum group elements (PGE). Rare earth elements and cobalt needed for electric vehicles have also been found in the Arctic regions of Russia and Scandinavia.

The Arctic is estimated to hold nearly 22% of the world’s undiscovered oil and natural gas reserves, with Russia accounting for 52% of the Arctic’s total energy resources and Norway holding 12%.

However, it’s possible that, despite Russia being a major producer of cobalt, chrome, copper, gold, lead, manganese, nickel, platinum, tungsten, vanadium, and zinc, a shortage of critical raw materials is one reason for its interest in the Arctic.

.

.

According to Defense Blog, hackers obtained access to classified presentations outlining Russia’s mineral resource development strategy through 2035.

The documents expose Russia’s growing dependence on imported raw materials and its declining domestic resource base:

The documents indicate that Russia is struggling to compensate for the depletion of its mineral reserves. Over the past 25 years, the discovery of new deposits has declined tenfold, and the extraction of strategic minerals has outpaced their replenishment…

One of the most alarming revelations is Russia’s near-total dependence on imports for key industrial metals. The country lacks sufficient domestic reserves of manganese, chromium, lithium, cobalt, and copper—essential components for modern technology, defense, and infrastructure. Some of these, such as lithium, have become even more inaccessible following the loss of Ukraine’s mineral deposits. Russia’s supply of cobalt, crucial for military electronics, relies almost entirely on foreign sources, making it vulnerable to economic sanctions and geopolitical disruptions.

Government investment in geological exploration has also seen drastic cuts, with funding reduced by 94 billion rubles. Private sector investment has not been able to fill the gap, further weakening efforts to secure new mineral deposits. As a result, Russia remains largely dependent on exporting unprocessed raw materials. Oil, gas, coal, and iron ore account for more than half of the country’s total exports, underscoring its failure to diversify its resource economy.

The leak also sheds light on Russia’s intensified efforts to secure raw materials from foreign suppliers. In response to shortages, Moscow has ramped up critical mineral imports from China, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Mongolia.

Continued in Part II.

Tehran Institute For International Studies tiis

Tehran Institute For International Studies tiis